I sent a long letter about Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward to my cell biologist friend, who suggested I write an article for a magazine. At the very least, I thought, I should write something fern-related for this very-neglected blog! So this is a book report of sorts, of this FANTASTIC book by Luke Keogh:

This is the first whole book that features N.B. Ward, inventor of Wardian Cases. Mr. Keogh has done a tremendous job of research. Prior to this book, the only mention I could find of Mr. Ward was in a smattering of gardening websites as the inventor of the terrarium—which is true, but he was SO much more. That was the indoor Wardian case, which had its own influence, but the outdoor Wardian case was used for over a century to transport plants on ships around the planet.

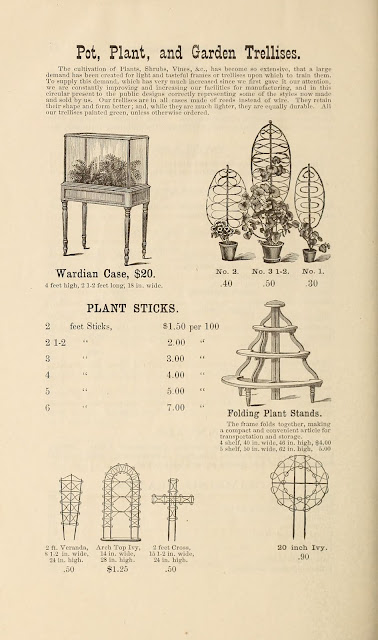

Ad for indoor Wardian case (not as ornate as some):

Fancier versions:

Readers of The Fern World will already be familiar with Mr. Ward because he meets Fernie and ends up sending her a Wardian case in Chapters 6 & 7. At the time I wrote that, I hadn't quite made the distinction between the sturdy, seafaring Wardian cases and the decorative Wardian cases for indoor refinement.

Here's an excerpt of from The Fern World, based on Mr. Ward's own account from his book, On The Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases.

Nellie had been right in her assessment of Mr. Ward. Fernie could perceive why he and Papa were friends and she was glad. He was jolly and she was delighted to have made his acquaintance. It would be just a bit of time before Mr. Ward was to reveal the invention of his famous case that did, indeed, grow ferns. However, it was inspired by his interest in a Sphinx moth “cocoon” and not ferns. Ferns, it would turn out, were a very happy accident that would go on to inspire the import of plants from around the world! Tea plants made their way from one region of India to Ceylon, bananas came all the way from China to the tropics, and rubber trees would make their journey to far-off places. Indeed, it is much thanks to Mr. Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward for his Wardian cases, that we have such a world that we can house tropical plants indoors; including many species of ferns.

He was a doctor and amateur botanist. When he was 13, he expressed an interest to his doctor-father about wanting to study plants and his father put him on a boat to the West Indies to cure him of this ridiculous notion. As you did, back in those days. Ha! He never lost his love for botany, but he dutifully followed in his father’s footsteps as a doctor and inherited his practice, located in smoggy, coal-choked London near the docks. He treated all kinds of patients, and spent his days rising early and botanizing before seeing patients.

More than medicine or botany, he was interested in all things scientific and of the “natural” world. He founded the Microscopical Society in 1839 with Natural History publisher John van Voorst. He also was a member of the Apothecary Society at Chelsea Physic Garden. All doctors at the time had to understand botany and the medicinal properties of plants. (Imagine that!) So his work as a doctor was not too far removed from botany. He oversaw examinations for medical students for many years. He also was instrumental in getting the society/garden to admit women, which was outrageous and deliciously radical for the day!

The first experiment with the Wardian case was in 1829 with plants sent from London to Australia, which only took 6 months. Ha! And the plants survived, and Australia reciprocated with some native ferns and other exciting plants. And the people who took notice were . . . botanists, gardeners and nurseries. That started a lucrative, exotic plants trade.

As a physician, he testified and worked to repeal the British glass tax and said that lack of light had a negative health effect on the poor, who were stuck in dark, dank houses. He was successful, and that brought literal LIGHT to homes and buildings everywhere. It also ushered in the building of more greenhouses, window garden units, as well as indoor Wardian cases (terrariums for ferns).

Mr. Keogh has filled in so many gaps about N.B. Ward, especially regarding the impact his invention had on the world. The Wardian case broke the monopoly China had on tea and Brazil had on rubber. Botanical espionage and Wardian cases snuck out of both those countries to make their way to India to create plantations that exist to this day. It changed our farming practices and encouraged botanical gardens, and changed our diets. Tea, coffee, bananas all became cheaper and more accessible. On the downside, it encouraged economic incentives for colonial plantations, and the spread of invasive species (pestilence, vermin, and plant). "Exotic" mimosa trees from China and Kudzu from Japan are a nuisance 100+ years later. Personally, I love mimosa trees! And Kudzu is actually where arrowroot powder comes from.

From all accounts I have read in primary sources from the time, Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward was a congenial, kind, generous and humble man who genuinely cared for his patients, friends, family and colleagues. He maintained friendships and connections with other scientists in his native Great Britain, as well as around the world (America, Australia, India, etc.) He was a member of several societies, regularly holding weekly soirees with eminent scientists of the day, and was supportive and encouraging of other’s ideas and work. A letter to Darwin from A.R. Wallace said something like, “I spoke with a Mr. Ward and he suggested . . . .” So far I’ve not found any letters from Darwin to NBW, but I do know that he was one of the sciencey people that Darwin sent his Origin book to when the third edition was printed.

I'll have more on NBW in another post in which I share his letters and personal writings. I read on one website that "not much is known about Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward." Thanks to the hard work of Luke Keogh, this unknown scientist is better known!

No comments:

Post a Comment